Selected Reviews of Black-and-White Photographs on Exhibit:

Mind Space

Tim Kilby’s exhibition of photographs at the Intuitiveye Gallery (641 Indiana Ave. NW) is his first in the area. In it, Kilby demonstrates indebtedness to Ansel Adams, Minor White and others both in subjects, point of view and technique. Thus the photographs of rock textures are not much more than advanced student exercises. But numerous images in the show give evidence of an emerging independent vision—a tour-de-force double exposure photograph of a starry night in the mountains that honorably stands comparison to Adams’ most famous picture, “Moonrise, Hernandez”; a chilling photograph of a dog frozen in the woods; a couple of very beautiful landscapes; and a picture of a gracefully curving metal patterns in a soft, white light. That adds up to an impressive beginning. Through Jan. 4.

Forgey, Benjamin. “Review | Galleries,” Washington Star, December 10, 1978.

Frozen Dog

. . . [T]he companion exhibition of “Still-Life Photographs,” featuring newly acquired work by several contemporary photographers (happily, many from the Washington area), takes on added importance as a statement about the resurgence of interest in both still-life and realism in current photography. It also indicates a far greater range, both visually and emotionally, than that observed in the pristine, largely decorative paintings from the past.

For example, [William Michael] Harnett’s [1882 trompe l'oeil] “Plucked [Clean]” may be amusing as history but comparison with Tim Kilby’s poignant photograph of a frozen dog lost to an ice storm shows a far deeper awareness and sympathy with life. It may be cold outside, but it is far colder standing in front of Kilby’s chilling photograph. Kilby is also concurrently showing solo at the Intuitiveye Gallery. . . .

Lewis, Jo Ann. “Review | The Object as Subject: Creative Packaging at the Corcoran,” The Washington Post, January 6, 1979.

Commentary on Constructivist Color Photography:

Timothy J. Kilby of Sperryville, Virginia, has been chosen to be a recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts 1981 Photographers’ Fellowship in the Southeast.

The grant, which is based on artistic achievement in the field of still photography, will enable fellows to purchase time and materials to further their careers in the arts. Timothy Kilby was one of only 52 recipients out of 2066 applicants nationwide for this year’s awards. In addition to continually producing new works, Tim is Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art at Lord Fairfax Community College in Middletown.

Art News, Virginia Commission for the Arts, vol. 5, no. 2 (March 1981).

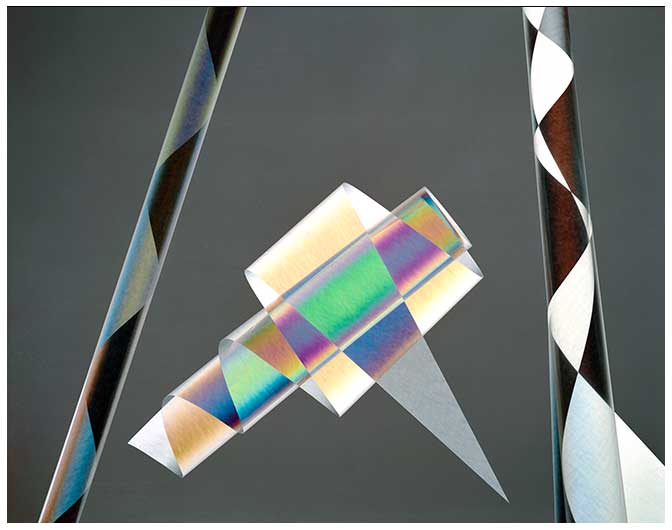

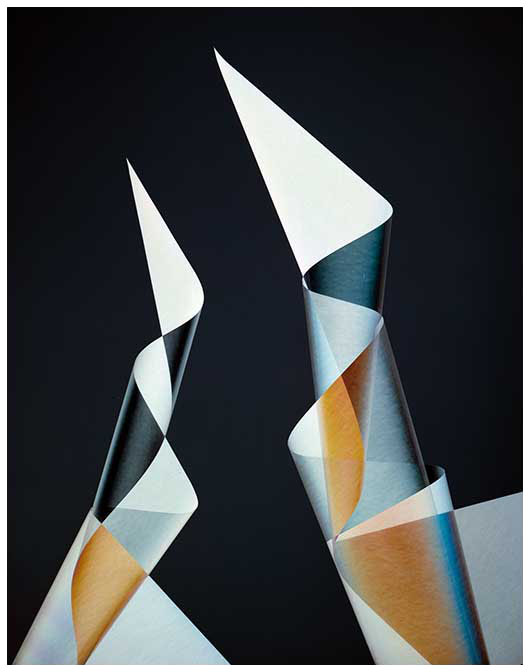

Composition Twenty-Two

An Emerging Artist Fellowship, a rare item these days, was recently won by one of Virginia’s young photographers, Tim Kilby, a 33-year-old rural Virginian currently living on his family farm in Sperryville. A former Army photographer, he presently is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art at Lord Fairfax Community College in Middletown. Prior to working on his MFA at RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology), Tim had applied for NEA grants several times with what he admits himself as “embarrassingly poor-quality work. I learned in the beginning to expect lots of rejections. Nothing has changed; I still get dozens of rejection letters for shows or support. One becomes desensitized after a while. I don't spend that much time soliciting shows, a preoccupation with many artists. Self-understanding and fulfillment are more important to me than fame. I'm not a competitive person, and I'm not afraid to share my experience with others. I just try to be the best artist I can be. And I'm happy with that." After a rather intense year of reflection and post thesis research, he began work on a body of color work—this was in late 1979—and this work, as he puts it, was “built upon a carefully constructed foundation." These efforts were rewarded by recognition from curators as well as from the NEA. His works have been included in exhibitions at such prestigious places as the International Museum of Photography—George Eastman House, the Friends of Photography—Carmel, California, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Several collections in such locations as George Washington University, Museum de Arte de Sao Paulo—Brazil, the Corcoran, RIT, and the Virginia Museum include his photographs.

To supplement the photograph of Tim’s work, we’ve included excerpts from one of his letters which will serve to introduce you to his theories and process.

"I shall briefly describe my mechanical technique and aesthetic premises.

Yes, these photographs do look like paintings. But that is a problem of the viewer’s perception of the media. The visual syntax of painting—other visual media are included here—and that of photography are identical. This can lead to confusion if the expectation of differences exist[s]. It is the philosophical outlook and mode of operation that separates the media.

My cellophane constructions are illuminated with polarized light. A polarizing filter on the camera creates the color as seen on the ground glass. The composition is seen in its entirety, and then it is accepted or rejected. Individual components cannot be altered separately as in other visual media. When one color changes, all colors change accordingly. When the ground glass image appeals to the eye and psyche, the exposure is made. That ends the creative process. Unlike the altered print, there is no manipulation of negative or print. The process is purely photographic, an immediate response without subsequent alteration.

Artistic preconditioning tells us that abstract subjects belong to the other media. There is no prerequisite that the object before the camera be familiar or even recognizable, though this most often is the case. My works are not a challenge to traditional styles or subjects. The images merely come from one sometimes forgotten fact of the photographic medium.

This selection of color images is from a much larger body of recent color work. I consider my color work not unlike my early black-and-white photographs which revealed conceptual content through traditional landscape subjects. Time will tell whether these images succeed in confirming my belief that the medium is not defined by the subject and that Art exists beyond the specifics of the various media. The works I produce must be judged on their own merits as photographs because, in the fullest sense, that's what they are."

Marsha Polier, Virginia Society for the Photographic Arts, July 1981

Tim Kilby’s cellophane cone constructions under cross-polarized light look more like drawings than photographs.

Ostrow, Joanne. “Review | Focus on Photo Shows: Patterns in Light and Shadow,” show “Configurations” at Dimock Gallery, Washington Post, July 24, 1981.

Artists are never static. They change styles, mediums and message as they refine and polish their skills.

The exhibit by Rappahannock photographer Tim Kilby that opens this weekend at the Middle St. Gallery in Washington proves that point—or at least part of that point.

Kilby’s show includes the realistic black-and-white photography for which he has won acclaim over the past several years. It also features his abstract color images, described by reviewers as “a new way of creating constructivist art.”

To viewers, the two blocks of work look like two different shows, an example of how the artist changes style, medium and message. But to Kilby, only the first two components are different. “I agree that they’re very different visually, but the emotional quality is the same, so I don’t see the two as being quite so different as others see them. I get the same pleasure, the same fulfillment from the color work as the black-and-white realistic shots. That’s why I don’t see that vast difference.”

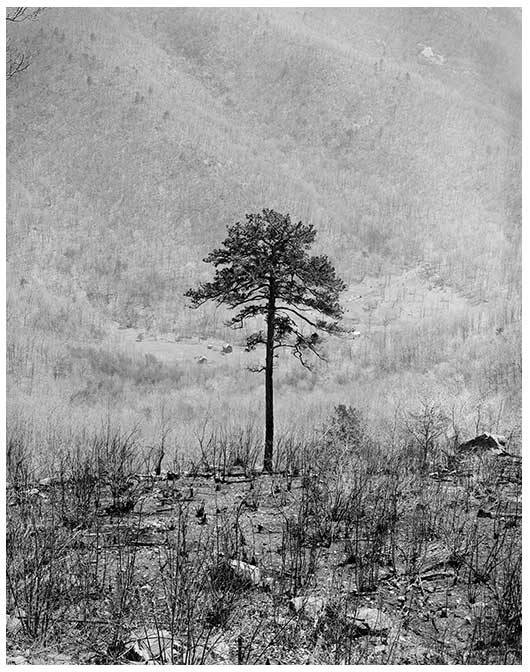

Lone Pine

The black-and-white photographs depict landscapes and objects from around Rappahannock and the Blue Ridge foothills. “It’s not just a repetition of everyday life but rather things that people might have seen if they’d stopped and looked,” Kilby explained.

A close-up of tall grass in an unmowed hay field, a speck of snow tucked away between the blades, has the same feel of flowing movement, the same texture as a woman’s windblown hair.

A shot taken from the heights of the Shenandoah Park, an otherwise ordinary scene captured a hundred times by amateur shutter-bugs armed with Instamatics, is transformed into art by Kilby: He creates stark contrast by framing a single pine tree, survivor of a fire, in the foreground of the vista of farming valley and hillside forest.

In one of his most famous prints, accorded high praise by Washington, D.C., art reviewers, a view of the stars at night becomes a skyscape, mountains silhouette on the horizon.

Creative Fine Art

His color work is difficult to describe. It creates emotions rather than ideas with the same punch delivered by the abstract artists who work in oils or acrylics.

Composition Twenty-Four

“I studied color photography, and I did some commercial work but I really disliked all the color that I had done. So, I went back and studied color photography again. I studied art in all mediums. And I came to conclusions on what I felt, what I knew about color, and decided I liked the abstract but not the realistic.”

His medium is unique, a combination of subject matter (bits of cellophane) and lighting that results in images more often found on canvas. “I don’t feel the technique is so important. But it is a fact that no one is using the technique I use; it is still a photographic way of looking at a scene, of composing. There’s no darkroom trickery at all. It’s just unusual subject matter,” Kilby said. “It’s fine art in the creative sense.”

Kilby has been doing this constructivist art since 1980 with impressive results. A half dozen galleries, including the Corcoran in Washington, D.C. and the Virginia Museum in Richmond, have purchased his color work. He just finished a major [solo] show in Winston Salem, North Carolina, and shows in a [group] exhibit now hanging at the Museum of Art in Eugene, Oregon.

Kilby’s abstract compositions convey a festive feeling, a feeling of harlequins and carnivals, New Year’s Eve parties and Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

“That’s a response I get from a lot of people,” he acknowledged, smiling. “I’ve picked playful colors and even playful titles for some of my work. For instance, “Four Notes Dancing. I was thinking of the playfulness of music, the liveliness, and I tried to translate that visually."

. . .

Rappahannock News, Washington, VA, June 23, 1983